Preface/Disclaimer: This was predominantly written before Vivienne Westwood’s passing. I am in no way trying to discredit her; she has been, and always will be, one of my favorite designers.

For decades, subcultures like punk, grunge, and goth have been a muse for high-fashion houses and fast-fashion brands. With the origins of these subcultures being working-class youth, this inspiration (or appropriation) marked a massive shift in fashion and the way trends are formed. But in the following decades, as more brands referenced punk, any semblance of what punk was had become extremely convoluted, to the point where the current trend of “modern punk fashion” is unrecognizable from its origins. This process closely resembles the four stages of hyper-reality Jean Baudrillard set out in his 1981 book Simulacra and Simulation. This appropriate is being labled as “the death of punk” or “the death of subculture”.

Following World War Two, the world boomed in countercultural youth groups. Within these groups, members dressed, talked, and thought alike. The first of these groups was the Teddy Boys, or “Teds.” The Teddy Boys were British working-class teenagers infatuated with American genres of Jazz, Skiffle, and, later, early rock-and-roll. Teds were easily identifiable by their dark blazers or drape jackets, with velvet trim or lapels, tight “drainpipe” jeans or trousers, and chunky leather oxfords. This subcultural uniform was an attempt to imitate the “zoot suit” popularized by jazz musicians in the 30s and 40s. Teds were also known for their reckless attitude, often forming gangs and brawling with each other, cops, and unsuspecting citizens. In an interview with Rolling Stone, an English man spoke about the Teds, saying, “London doesn’t remember them with any fondness. You know those little caps Gene Vincent wore—Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps? The Teds used to put a razor blade in the bill and use the cap as a weapon in fights. Those crepe-soled shoes they wear, they had razor blades sunk in the toes. No, London doesn’t remember the Teds with any fondness.” Like the Teddy Boys, most subcultures form around music, and though the Teddy Boys are mostly forgotten, they play a crucial role in how future subcultures would arrange themselves.

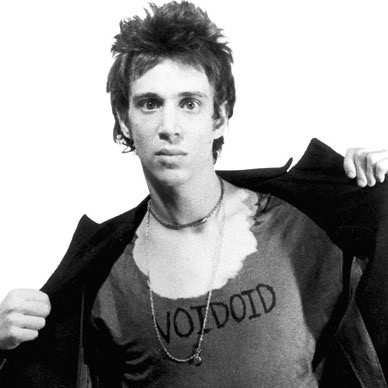

In the 70s, we started to see the formation of what would become the most influential subcultures and one of fashion’s biggest muses for decades to come—punk rock. Now the origins of punk rock are highly debated (please don’t message me about Death, or Los Saicos; while these bands may have had this sound before many of the bands I’m about to mention, they were unheard of at the time (you’re virtue signaling)). For the sake of this paper (which is not about the origins of punk), The movement we now know as punk started with The Ramones in Queens, New York. The Ramones formed due to a mutual love of The Stooges. In 1976 the band released their self-titled project taking inspiration from The Stooges, The Velvet Underground, The Sonics, The Kinks, and many other bands we now label as proto-punk. It had an aggressive vocal and instrumental style and lyrics that contained themes of violence, angst, nihilism, and an aversion to authority, all of which would become common themes in punk lyrics. This album would set the tone for the sound of underground music in the following decades. It would be built upon by bands like the Sex Pistols, Johnny Thunder & The Heartbreakers, Richard Hell and The Voidoids, The Clash, etc.

Like the origin of the sound, the origin of punk fashion is often argued about and misattributed. Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren are often attributed with “creating” the punk style with their store “Sex,” their brand Seditonaries, and their styling of the Sex Pistols. This ignores McLaren’s biggest inspiration, and in my opinion, the actual creator of punk style, Richard Hell. McLaren first met Hell in 1975 when McLaren was managing the New York Dolls. To quote McLaren himself, “Hell was a definite 100% inspiration…being inspired by (him), I was going to imitate (him) and transform it into something more English.” When McLaren returned to England, he added some inspiration from Hell to Vivienne Westwood’s designs. This marked the first of many appropriations of punk and its fashion and the first step in Baudrillard’s four stages of the simulation.

In Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard writes about a phenomenon he called “hyper-reality.” Hyper-reality occurs when something meant to simulate something or a “simulacra” effectively becomes the thing it was meant to simulate in the minds of the masses. The example he gives is the 1978 miniseries Holocaust; a show meant to simulate the real-life event of the Holocaust. So, when thinking of the Holocaust, people think not of the actual Holocaust (because they were not there) and will instead think of the miniseries. The simulacra become the thing it meant to simulate, becoming its own “pure simulacrum.” As previously stated, this process happens in four stages (these stages eventually becoming a meme format as seen here). The first stage of this process would be Richard Hell himself, the originator. In the second stage, a simulation is created to reflect the initial one, but is slightly distorted; this happened when Malcolm McLaren started creating clothes with Vivienne Westwood inspired by Hell’s style, but exaggerated, and “more English”, becoming the first punk designer. In the third step, the process is repeated, and a distorted simulation is created, this time based on the simulation of the previous step, not the originator. This is done by brands like Dolls Kill, Hot Topic, or Spencers. At this stage, any connection to actual punk style is beginning to be lost as distorted simulations are created, inspired by other distorted simulations and “punk fashion” begins looks more Avril Lavigne than Richard Hell. Lastly, we have stage four: Once again, a simulation is created based on the previous stage, but in this final stage, any relation to the first stage becomes unrecognizable; a pure simulacrum has been create. This can be seen with the “modern punk” fashion trend on TikTok: Large font slogan tees, designer belts, skinny black jeans, and designer boots bear no resemblance to Richard Hell’s style of tattered second-hand garments held together with pins and cheap sewing(done not as a fashion statement, but out of necessity). For most young people, if you ask them to describe punk fashion, they’ll tell you it is something akin to the last two steps and give examples like Machine Gun Kelly or Avril Lavigne, maybe Vivienne Westwood. In the minds of these people, punk fashion has been replaced with these simulations, creating a hyper-reality.

Mclaren and Westwood’s work also marked a huge change in the way fashion trends were created. Traditionally, trends were created by high-fashion brands, then adopted by middle-tier fashion brands, then by affordable fashion brands. When the trend was finally accessible to the working class, the bourgeoisie were already onto another trend, not wanting to be associated with a trend now accessible to working class people, restarting the cycle. This is known as the trickle-down fashion theory. Trends were created by high-fashion brands and would trickle down. But Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren taking inspiration from people like Richard Hell shifted fashion towards a trickle-up theory, where fashion brands took inspiration from the working class, not high-fashion brands. This is much more popular now and can be seen with most major fashion houses today, whether its Balenciaga’s exaggerated norm core, the popularity of distressing, and many designers taking inspiration from vintage garments easily found in thrift stores. No longer do brands create the trends to sell us, because this flip, we now create the trends, and brands are forced to conform.

It’d be easy to say that the appropiation punk fashion doesn’t matter (because it really doesn’t), but for subcultures, fashion is more than just a way of expressing one’s self; it is a way of signaling to others your “membership” of a subculture and subsequently your ethics. So when anyone is allowed to pretend that they’re a part of a culture without sharing the values of said culture, the sense of community is lost and this music becomes just a genre anyone can listen to. Punk, as a subculture, always had its morals and ideals, such as anti-authoritarianism, anti-corporatism, a DIY attitude, and often supporting progressive direct action and mutual aid movements. These shared ethics made punk more than just a genre of music; it was a way of life that affected everything you did. The best example of this would be the invasion of Nazis into the punk scene with their opposing politics, it ended poorly, resulting in songs like the Dead Kennedy’s “Nazi Punks Fuck Off,” or resulting in violence. For subcultures, gatekeeping is essential to preserving their sense of identity and comradery.

When talking with my friend about this paper, he mentioned a similar paper he wrote but never published for a now-defunct magazine run by two of our friends. His paper was titled “Necrophilia” and also discussed this appropriation of punk and the influx of posers, he argued that punk has been dead for a long time and that anyone trying to participate in it now is just metaphorically fucking its dead corpse (hence the name). Contrary to the title, I do not actually think punk is dead, nor do I think it will die, despite shrinking in popularity over the years. Any area with a population of young people is bound to have somewhat of a “scene”. This influx of posers is not a new thing; though, there have always been posers, not just in punk but in all subcultures. Like with the Nazis (but much less offensive in this case), outsiders who do not share, respect, or understand the culture behind punk are trying to break into or pretend to be part of something they are not. The only difference in this circumstance is the scale of this influx. With the “modern punk” style and the rising popularity of alternative genres and subgenres, there has been a boom in internet “punks”, whose only connection to the genre is attempting to dress like what they think a punk should look like. Though most of these kids will soon move on to the next trend, chasing the high of trendiness, some of these kids will actually connect with the genre and culture and become the next generation of punks, keeping the genre alive.

Work Cited

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press.

Chang, R. (2012, September 13). Proper English: The teddy boy suit and its Tiny Revolution. Vol. 1 Brooklyn. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://vol1brooklyn.com/2012/09/12/proper-english-the-teddy-boy-suit-and-its-tiny-revolution/

Epstein, A. (2015, December 11). Richard Hell, reading at the University of Sussex in the UK (2/4/14). Locus Solus: The New York School of Poets. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://newyorkschoolpoets.wordpress.com/2014/01/24/richard-hell-reading-at-the-university-of-sussex-in-the-uk-2414/

Gaines, D. (n.d.). Ramones. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/ramones

Gordon, Milton M. “The Concept of the Sub-Culture and Its Application.” Social Forces, vol. 26, no. 1, 1947, pp. 40–42. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2572602. Accessed 19 Nov. 2022.

Hopkins, J. (2018, June 25). Beatle loathers return: Britain’s Teddy boys. Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/beatle-loathers-return-britains-teddy-boys-119244/

JustOrdinaryMan. (2022, September 26). Four stages of simulation. Know Your Meme. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/four-stages-of-simulation

Kelly, E. (2021, November 4). 25 vintage pictures of Britain’s real-life ‘Clockwork orange’: The stylish and violent Teddy boys. All That’s Interesting. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://allthatsinteresting.com/teddy-boy

Melody Note Vintage. (n.d.). Punk Fashion History. TikTok. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.tiktok.com/t/ZTRVjQAEH/

PHILOnotes. (2022, November 9). What is subculture? YouTube. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BwBWlRFs8D8

Richard Hell History. Punk77. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.punk77.co.uk/groups/richardhellhistory.htm

Simulacra and simulations. Baudrillard Simulacra and Simulations. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://web.stanford.edu/class/history34q/readings/Baudrillard/Baudrillard_Simulacra.html

Subcultures and sociology. Grinnell College. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/subcultural-theory-and-theorists/what-is-a-subculture/

Trash Theory. (2022, January 22). Before 1976 revisited: How punk became punk. YouTube. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://youtu.be/6lyoAczdMSM

West, S. (2018, October 24). Philosophize this!: Episode #124 … simulacra and simulation on Apple Podcasts. Philosophize This! Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/philosophize-this/id659155419?i=1000422541771

What is subculture? FutureLearn. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/intro-to-japanese-subculture/0/steps/23560

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, December 29). Skiffle. Wikipedia. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skiffle

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, January 23). Teddy boy. Wikipedia. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teddy_Boy

Leave a comment